Skeleton in the Closet

Early in the process of photographing this series, I showed some preliminary images to another photographer. She paused, closed the portfolio, and said, “I’ve seen thinner.”

I was taken aback. “It’s true,” I replied. “Some of these men and women are healthy now. Some are very sick, and yet look healthy. Some people, even with anorexia and bulimia, can be quite heavyset. And some people who look quite normal—people you know, even—have an eating disorder hidden in their history.”

. . .

I’ve seen thinner. We all have: the emaciated bodies, the walking skeletons, the withering models. Many of the women and men in this series have looked this way before; some still do. Beneath the layers of clothing and confusion is skin stretched over bones, which they are loathe to reveal. They have, as it were, a skeleton in the closet.

These photographs are about normal people, people like me. I attended college right out of high school. During that first winter away from home, I began to find myself depressed, lonely, and in poor physical condition. This went on for some time until, finally, at the college nurse’s suggestion, I went to talk with someone in the counseling center. The counselor was gracious, asked good questions, and listened well. Over the course of the next few months, we were able to unravel the tangle of my thinking, and along the way discovered that, among other things, I was anorexic.

That word hit hard. I had never really thought about anorexia, and certainly never thought of myself as someone susceptible to it. I had assumed that eating disorders were for women who didn’t like their appearance. With some research, however, I discovered that anorexia is more about issues of control, which did apply to me. I was a quiet, intelligent achiever, and I didn’t want anything to get in my way—least of all food and thoughts of food. Over the course of that year, I was able to move forward, leaving the disordered thinking and eating behind.

. . .

These photographs are about normal people, who sat down with me over coffee, and poured out their secrets. They told me stories of abuse, neglect, insecurity, cruel and thoughtless words, terrible things they’ve done to their bodies and families, the results, the healing process, the enduring ache within. They told me, a complete stranger, things they have told no one else. I was often their confessor, their confidant, their priest.

I’ve seen thinner isn’t merely a phrase uttered by those who view this work; it is also often the mantra of those who suffer from eating disorders. It is their constant obsession, the drive behind their efforts to control their lives and minds and bodies. They’ve seen thinner models, actresses, parents, friends; they’ve seen themselves thinner when they were younger; they’ve seen thinner clothes; they want to fit in.

They want it so badly that some are willing to die for it.

Even the briefest perusal of pro-anorexia literature reveals how driven, competitive, disciplined, and anxious eating disorder sufferers can be. Their walls are often plastered with glossy prints of thin models, their floors littered with magazines, diet books, exercise equipment, and scales. They’ve seen thinner, and it is their promised land, just a few more pounds away.

. . .

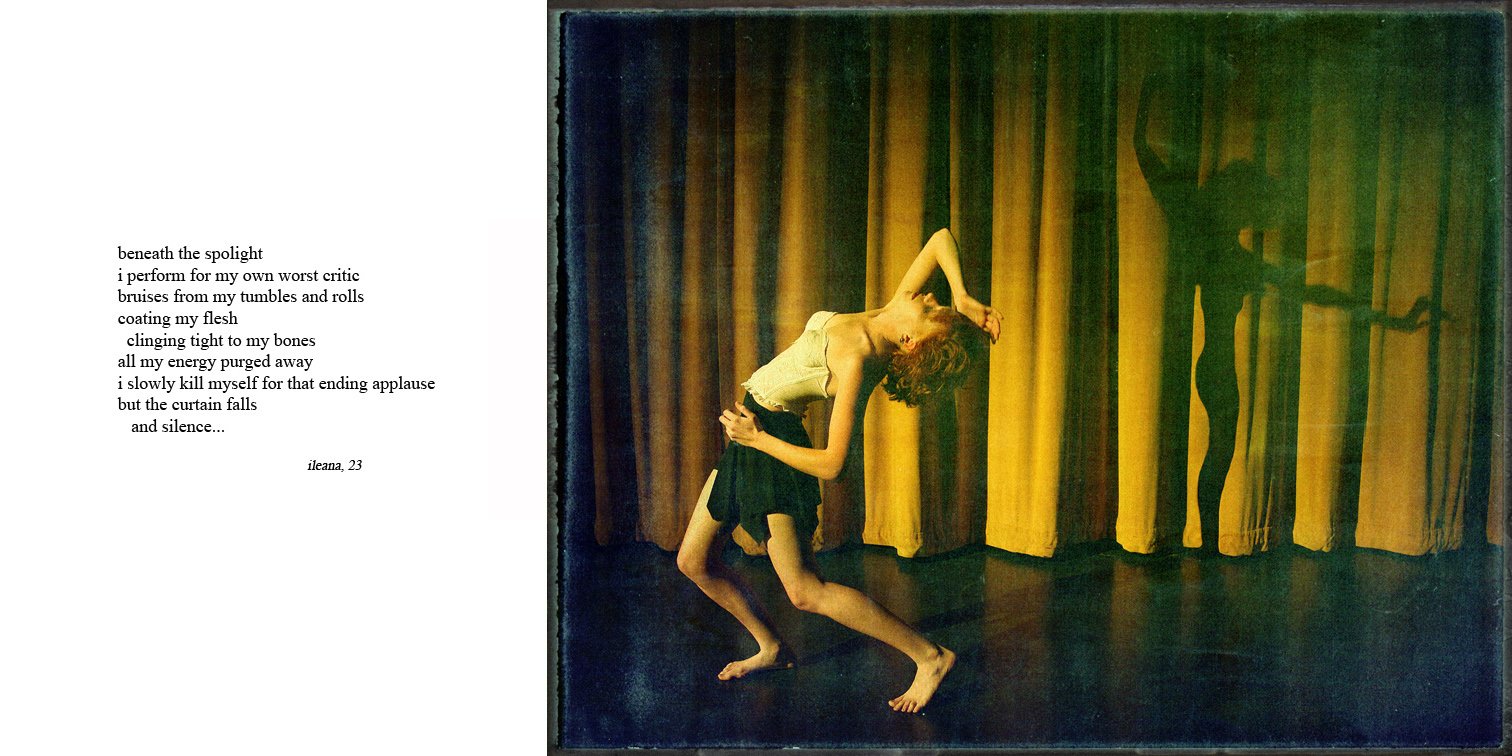

In a society saturated with shallow, narrow definitions of beauty, eating disorders are an increasingly prevalent trend. Movie stars, magazine ads, fad diets, pornography, fashion models, influencers…the pressure to look thin and attractive is an oppressive force that is difficult to resist. But obsession with appearance is not the only motivation for restrictive eating. For instance, dancers, gymnasts, wrestlers, and others, find themselves in unhealthy eating patterns in order to stay competitive.

Ultimately, the disorder is really a means for controlling one part of an often chaotic world.

According to the National Eating Disorder Association, 9% of the US population will have an eating disorder in their lifetime. Every 52 minutes, 1 person dies as a direct consequence of an eating disorder.

Eating disorders can start as early as age 6; according to studies, 40-60% of elementary-age girls are already concerned about their weight.

While anorexia may affect females from 6-96, it is generally confined to the domain of adolescents. Overall, however, one percent of females in America—one in one hundred—struggle with it. Anorexia Nervosa has one of the highest death rates of any mental condition; between 5-20% of individuals struggling with it will die.

Bulimia affects another 1-2% of adolescent and young adult women, while 1-5% of the general population practice binge eating.

These disorders are a silent epidemic; they are rarely discussed, fraught with shame, and often go undetected in those who suffer with them.

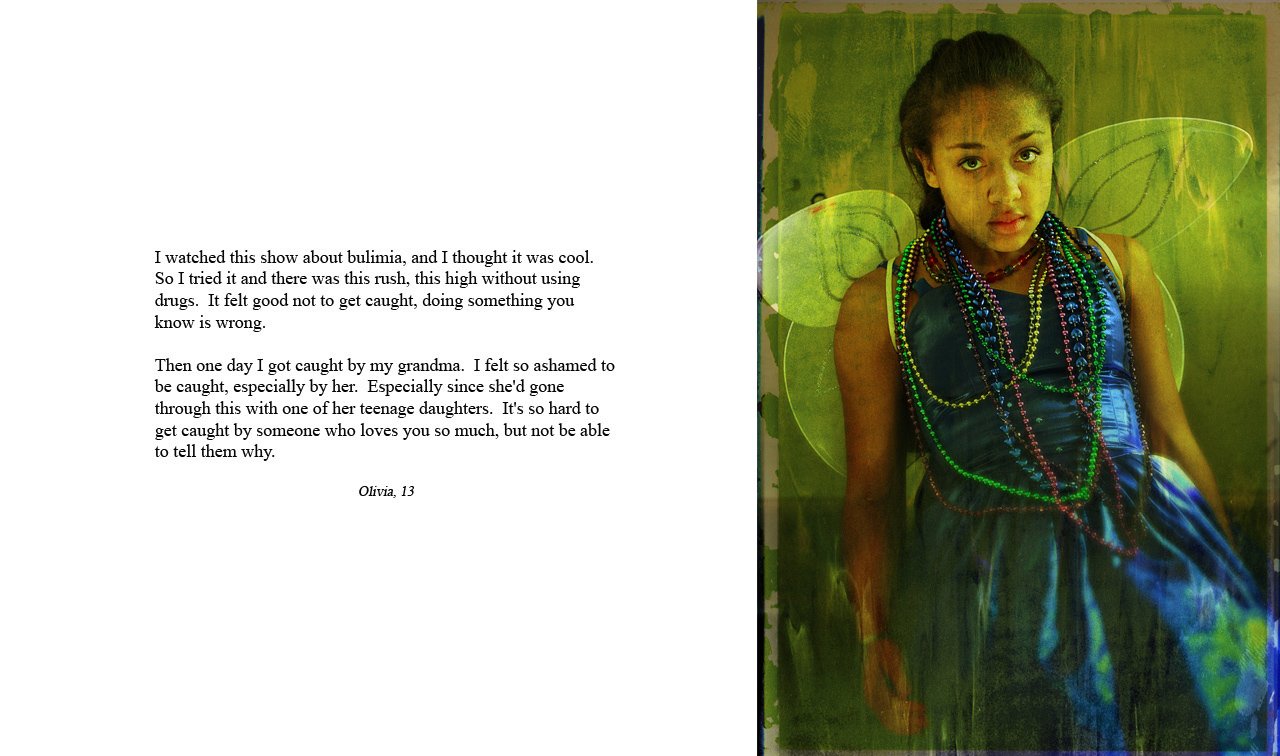

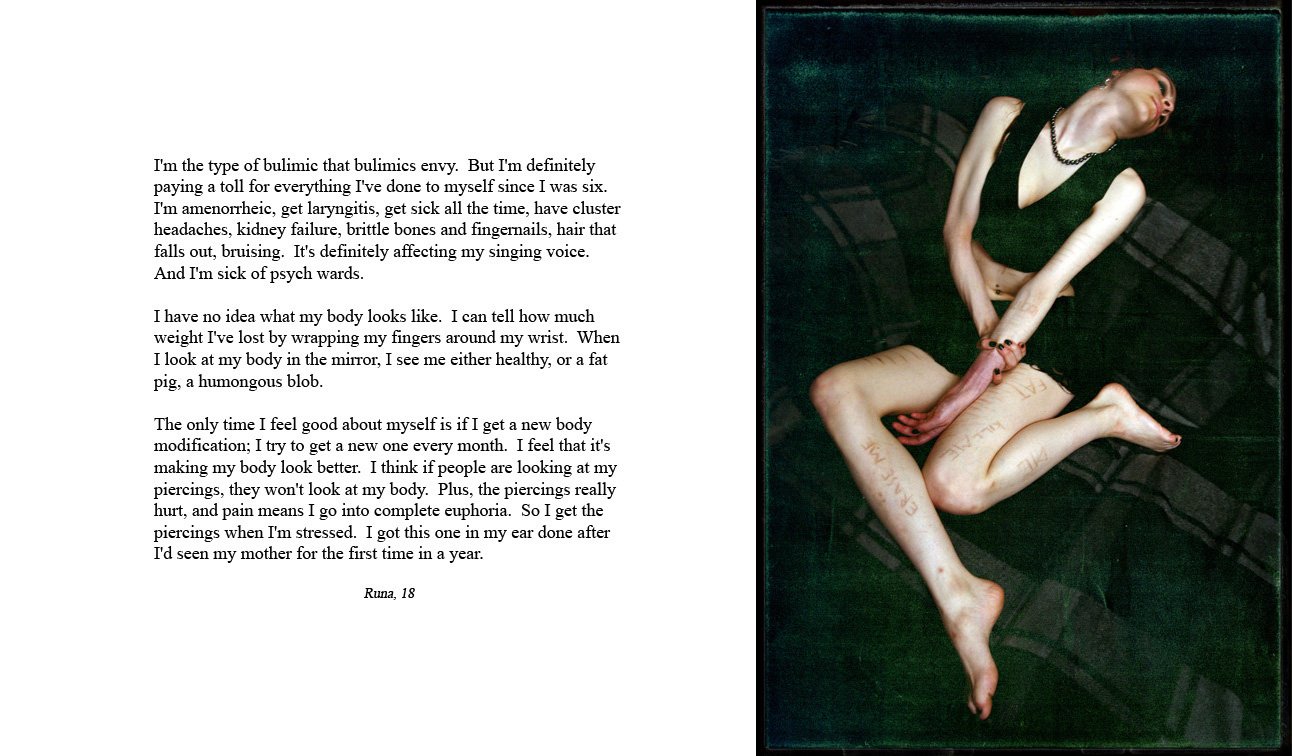

In the end, anorexia and bulimia are not about numbers or statistics, they are about specific people. Each of these people has a name, and a face. Their stories include their families, friends, counselors, classmates, their spouses and children. They are struggling for control over their bodies, their minds, their lives; for most, it will be a lifelong struggle.

These are the stories I am here to tell.

Viewed together, these small stories and portraits combine to make a single whole, as small chapters make for a larger novel. As you read through them, you will notice themes emerging: loss, hurt, cruel and thoughtless words, addiction, abuse, hope, healing. Perhaps the clearest theme is also the simplest, one which all of us would also acknowledge: the desire to be known and loved for who we are.

About the Project

The stories

This series is comprised of over 75 portraits and stories. Please click into the images below to read a few; if you’d like to view the whole series, and read the moving essay by author Gina Oschner, please consider purchasing the book from Amazon.

Skeleton in the Closet’s intimate portraits of women and men struggling with the secrets of anorexia and bulimia is both fine art monograph and memoir. Combining compelling photographs and personal stories, it gives the reader a compassionate, first-person look inside the minds of those who live with and try to leave behind an eating disorder.

Artist Fritz Liedtke—who relates the story of his own struggle with anorexia in his introduction—has created an award-winning series that includes women and men of all ages and ethnicities. This beautiful, full-color book is prefaced with a moving essay by author Gina Ochsner, and offers insight and hope to anyone wanting to better understand life with an eating disorder and the challenge of overcoming addiction.

The book is available through Amazon and other fine booksellers. Purchase your copy here.

purchase the book

show the series

Skeleton in the Closet is ready to show in your gallery, museum, or university. From the full set of images, an appropriate number of images may be selected to fit your space. Framed pieces are 16×20; the 5×7 text placard is hung next to the framed print. For galleries wired for sound, the show also includes an audio component, in which the stories are whispered at low volume, heightening the viewer’s sense of secrecy and constant internal dialogue experienced by the subjects in the series.

For universities, this body of work also lends itself well to cross-promotion and education. The series is appropriate for fine arts galleries, but also pertains to health, medical, psychology, women’s studies, and counseling departments, as well as the student life department. The exhibit gives universities a locus for arts and eating disorder awareness events, outreach, and education. Consider a collaboration that might include lectures, forums, and publications related to eating disorders. It also makes for an excellent opportunity for community outreach, and great PR.

The artist is also available for lectures. Please contact us for more information, or to schedule your show.

collect the limited edition portfolio

A limited edition portfolio of 14 images, overlaid with texts printed on vellum, is available. It is composed of:

Custom clamshell box covered in black bookcloth, with blind embossed inset leather label on the cover.

Title page printed on Arches Aquarelle 90lb Hot Press paper with deckled edge.

I’ve Seen Thinner introduction by Fritz Liedtke.

If Peter Pan Had a Little Sister essay by author Gina Ochsner.

14 Texts and Images: Texts printed on Legion Chartham Vellum, Images printed on Epson Exhibition Fiber Paper, all with archival inks. Each image is signed by the artist.

Colophon.

$5900, with a 10% discount for educational institution collections.